Why flexing about being a homebody is not good for your mental health

An increasingly popular perspective online among the young suggests that staying home alone, particularly by bed rotting, is morally superior to going out partying.Ìı

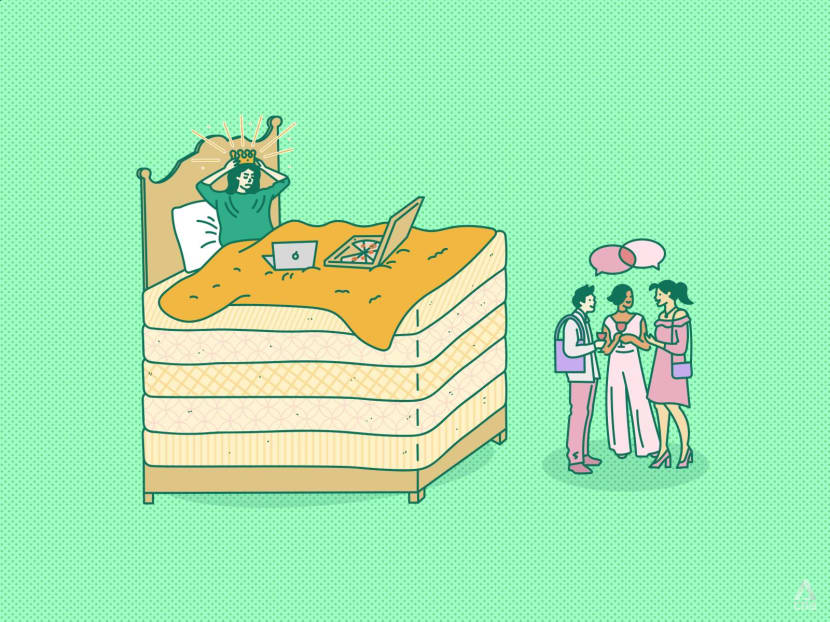

Psychologists cautioned against splitting into camps about how people maintain their mental well-being. (Illustration: CNA/Nurjannah Suhaimi)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

As personality tests go, the introversion-extroversion scale has always been a popular way to find oneâs tribe. But I remember the book by American writer Susan Cain that seemed to supercharge the introvert revolution â Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Canât Stop Talking.Ìı

The 2012 global bestseller essentially countered the widely accepted culture in schools and workplaces that prioritised saying something over having something to say.Ìı

It also helped extroverted peers understand the average introvertâs preferences, such as being a homebody and turning down party invites, that might have previously gotten us labelled aloof or unfriendly.

Like my fellow introverts, the ripple effect was initially understated, though it proved a force to be reckoned with eventually.Ìı

Almost overnight, society altered its perception about introverts, vindicating many of us from a lifetime of trauma of being cajoled to âspeak upâ and âdonât be shyâ.

However, this favourable stance appears to have taken on a more sinister slant in the last few years.Ìı

Even worse, it seems like weâre back at Square One â except this time, extroverts are on the receiving end of the judgement. In particular, bed rotting and similarÌısolo "do nothing" activities are increasingly positioned as radical acts of self-care, especially in cultures that have always extolled productivity.

Bed rotting is the act of staying in bed for extended periods of time doing passive activities that may includeÌıdoom-scrolling, snacking or binge-watching TV shows and movies. And its advocates see it as a way to recharge from from work, school or social obligations.Ìı

Concerns around bed rotting are not new, with experts cautioning that an excessive amount of time in bed could point to deeper mental health issues.

The issue now, though, feels more insidious: An air of moral superiority from those who engage in and encourage such solitary behaviour.

HOW SOCIAL MEDIA REINFORCES MORAL JUDGEMENTÌı

The writer of a viral post titled The Mainstreaming of Loserdom observed the changing ways that a younger generation talks about acceptable recreational behaviour.Ìı

The post highlighted a TikTok video of a woman saying that her favourite place to be was in bed watching shows on her iPad. The majority of the 40,000 comments echoed her sentiment. In another TikTok video, a man said thatÌıstaying home was his definition of a good time and that he did not need to go to clubs.Ìı

Relatedly, a viral tweet put this message across: âWeird how âliving lifeâ is associated with just stuff extroverts like to do.â

In short, bed rotting is in; partying is out.

¶Ù°ùÌıOng Mianli,Ìıa clinical child and adolescent psychologist, told CNA TODAY that such moral judgements tend to be rampant on social media because ânuance is harder to package into a viral postâ.

âSocial media thrives on binaries and moral judgements â ârest is superior to partyingâ or âsocialising is better than solitudeâ. This oversimplification creates unnecessary team rivalries,â the principal clinical psychologist in private practice at Lightfull Psychology said.Ìı

In my observation, the COVID-19 pandemicâs spotlight on mental health also fundamentally shifted the cultural zeitgeist around doing things alone, which may have once been touted as âloserâ or âfriendlessâ behaviour. Where the book by Susan Cain merely validated such personality traits, they were now seen as desirable.

Also, people inÌıisolation during the pandemic turned to likeminded groups online, whichÌıled toÌısocial media echo chambers. Many such circles did not just equate prioritising mental health with prioritising solitude, but tried toÌınormalise and glorify perceived acts of self-care without considering the extremities.

The danger lies in not realising when these simplistic views start becoming harmful, especially when one is âsiloed offâ, Dr Ong said.

âWhen everyone is in the same echo chamber saying that rest at all cost is good, itâs easy to mistake silence for safety and isolation for self-care. Itâs like wearing sunglasses indoors. We might think weâre protecting ourselves, but weâre just blocking out light that could help us see more clearly.âÌı

WHEN DOES RESTING BECOME ROTTING?

Even though the pandemic rewired societyâs relationship with rest and social interaction, rest is really just âa reprieve from overwhelming stimuliâ. It is akin to hitting pause on a movie, Dr Ong said.

âThe nuance lies in recognising when this pause becomes permanent, signalling deeper struggles like burnout or disconnection,â he added.Ìı

âBed rotting risks being misunderstood as inherently restorative for mental health ⦠For some, staying in became a form of safety, but this habit is now lingering in ways that may no longer serve them."

Yet, even when they are aware of the danger in bed rotting, some people may still feel like they are âreclaiming control over lifeâ and âvaluing personal comfort and mental peaceâ by choosing to stay in and opt out of activities, a psychologist cautioned.

Dr Annabelle Chow, principal clinical psychologist at Annabelle Psychology, said that lying in bed is often associated with getting some âme timeâ after a long day, so it is âeasy to underestimateâ the effects of bed rotting,

She also stressed that from a psychological perspective, bed rotting is different from âtraditional self-careâ, primarily because bed rottingÌıembraces passivity.

The glaring red flags are avoidance and isolation, signalling that rest has turned to rot.Ìı

When bed rotting happens multiple days a week, for instance, it can be seen as a pattern of behaviour that is used by the person to âavoid daily life, difficulties or coping with our emotionsâ, Dr Chow added.Ìı

âEspecially when it starts affecting your ability to keep up with work, family or school obligations, and whether you struggle with basic hygiene. These signs might suggest the presence of depression symptoms, which includes becoming withdrawn from social activities and the inability to meet oneâs daily responsibilities.âÌı

If left unchecked, bed rotting can then unintentionally reinforce that âit is âsaferâ to avoid the things that we are avoidingâ, Dr Chow said.

REST AND CONNECTION ARE NOT ENEMIES

Another obstacle standing in the way of balanced mental health is when you know bed rotting is bad for you but you are still reluctant to get help, especially if you believe that goodÌımental health and the hallmarks of hustle culture â such as working hard at the expense of self-care â cannot exist together.Ìı

Dr Ong cautioned: âWhen someone in that echo chamber even thinks about seeking help, it can feel like betraying the very identity theyâve built online â rest as rebellion or self-care as survival. Admitting that struggle feels like admitting defeat, and no one wants to feel like theyâve âlostâ.â

When everyone in the same echo chamber says that rest at all cost is good, itâs easy to mistake silence for safety and isolation for self-care.

In the long run, balance is key, though I believe this can be fully achieved only when we learn to recognise social mediaâs tendency to enhance extreme views.Ìı

âHustle culture says, âKeep going at all costsâ, while bed rotting culture says, âDo nothing and thatâs empowerment.â But both miss the middle ground of balance,â Dr Ong said.

Rest and connection are not âenemiesâ, but âcomplementary tools we need in different measures at different timesâ, he highlighted.Ìı

âBed rotting is fine as a temporary refuge from stressful situations, but it canât become a permanent residence. Rest restores, but itâs action and connection that give life meaning.â

As a fellow introvert who loves socialising, loves meeting new people, loves small talk, but prefers doing things alone and being a homebody, I understand the appeal of bed rotting.

Deeper mental health problems notwithstanding, the trend is, in some ways, about reclaiming an unspoken desire for more solitude that would have been previously judged as anti-social behaviour.

The problem starts when you believe that choosing bed rotting and other versions of alone time makes you a better person who is self-assured enough to buck the normÌıâÌıessentially mistaking preferences for principles.